ISLAMABAD: As young musicians make their way through a promising music industry in Pakistan to international platforms, emerging artists settled in northern areas of Pakistan struggle to make their name as their talent gains popularity with youngsters in the region.

HunzaNews March 19th, 2015.

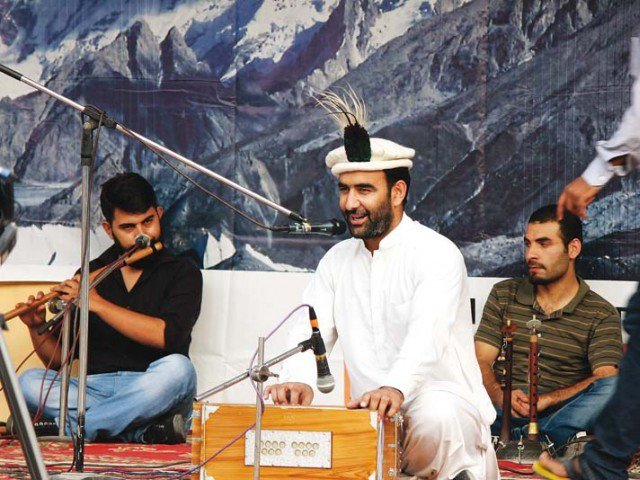

A rusted brown leather jacket rests comfortably on his broad shoulders concealing a traditional dark blue kameez-shalwar. Having travelled thousands of miles, Jabir Khan Jabir, a musician from Gilgit-Baltistan (G-B)had been on the road for two days. He arrives in the capital with an ambition to record his fifth music album at a private studio.

The 31-year-old singer’s kind face is masked with a vexed expression and deep set hazel eyes that narrate an immensely sorrow tale of the state of musicians from G-B. Although his father Babar Khan Babar was one of the leading singers of Gilgit city, his father did not want any of his children to pursue music as a profession.

“I was told that being a musician is not a respectable profession. But something from within, tells me that our hard work can change the mindsets of people and their views on music” says Jabir.

Despite the hesitation from his family members, Jabir continued with his journey and his four music albums have carved a niche in his hometown. Holding a bachelors degree, his passionate for music drives him. “I‘m not married only because I am already married to music,” he says.

As a music director and singer, Jabir uses a mix of local dialects of the northern areas, such as Shinah, Balti, Brusheski, Khuar, Urdu and Siraiki in his work. Specialising in folk and classical music, he composes his tunes with a flute, harmonium and modern instruments such as, guitar, saxophone and orchestra, merging them with the Rubab and other instruments.

His recent album Osek Bo means “just smile”. The album comprises poetry by Zafar Waqar Taj — a renowned poet of the area as well as the district commissioner of Gilgit city. The entire album is dedicated to the youth of Pakistan.

Delving further on the subject of melodies, he says, “Over time, people have started appreciating my music. It carved a niche market, mostly attracting a younger audience, who do not only appreciate music, but also want to learn it.” Impressed with the fervour of the youth, he says, “The new generation understands what I am trying to say. But the older members of the community still have issues.”

Jabir also received life threatening phone calls from unnamed authorities who said he was instilling western ideology through his music and corrupting young minds. “The threats made me want to work harder,” says Jabir.

After launching his first album, he managed to escape three attacks on his life. “Even if I lose my life, I will live through my music. “Musicians die, but music lives forever,” he says with a smile.

Jabir says that while the atmosphere remains conservative, his music magnetised women towards the council. “We even featured a female voice in our album which received a mixed response, some absolutely loved it while other locals criticised her inclusion,” he notes. “The women secretly come to the institution to learn. They will have to face serious consequences if caught,” he adds.

“We are now stuck in the middle. While the youngsters like the mix of both styles, the older generation feels that we are ruining the folk tunes by merging with new genres,” he explains.

Jabir aspires to continue making music in local dialects to preserve the languages. “This is the only way we can keep our tradition alive,” he asserts. “My poetry narrates peace — that’s just want we need in today’s day and age,” he says.

The Gilgit-Balistan Arts Council is now releasing local music on the internet. Since the past five years, the council has sent various local musicians to perform at international festivals.

Published in The Express Tribune,